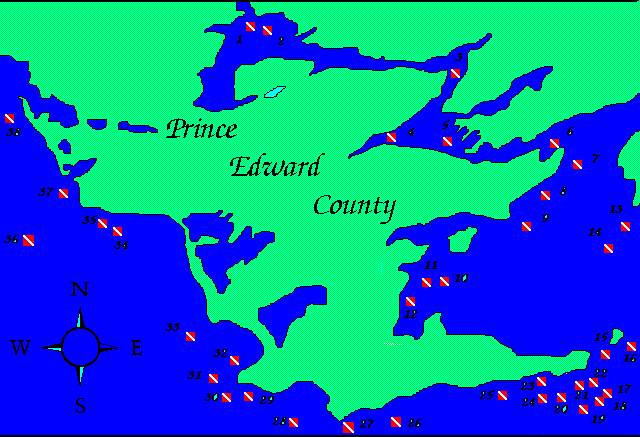

Pebbles is located at the east peninsular of Prince Edward County called Prince Edward Point. This unique location surrounded by Lake Ontario, proximity to the old capital of Canada (Kingston), proximity to the US and busy shipping routes between Toronto and Kingston meant that the Point had a unique location that served maritime communities well.

Prince Edward Point Lighthouse

The Prince Edward Point Lighthouse, also known as South Bay Point, Red Onion and Traverse Point Lighthouse is a square tapered wooden lighthouse with an attached dwelling. The lighthouse is located on the eastern tip of Prince Edward Point within South Marysburgh Township, Ontario. Besides the combined 7.8-metre (26 foot) lighthouse and keeper’s residence, the lightstation also includes a detached shed. The lighthouse was automated in 1941 and operated until 1959 when it was replaced by a steel skeleton tower. There is one related building on the site that contributes to the heritage character of the lighthouse: (1) the shed built between 1881 and 1926. Details.

Shipwrecks

Ships have in the last three hundred years had great trouble navigating around Prince Edward County and the Duck Islands. This has left the bottom covered with many interesting wrecks. Most of which are not marked. This adds to the excitement of possibly coming upon an undiscovered wreck.

The Marysburgh Vortex, found off Prince Edward County’s eastern coast, holds stories of unexplained shipwrecks, reminiscent of the Bermuda Triangle, from the age of sail and steam.

December 1882 .. SHIP AGROUND!

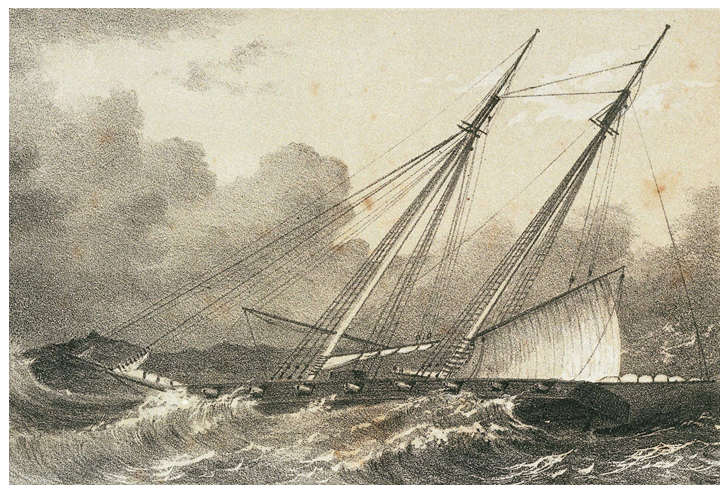

In December 1882, Capt. William VanVlack was at the helm of the schooner Eliza Quinlan. Laden with coal, the ship ran aground on Poplar Bar near Point Traverse Lighthouse due to high winds, fog, and snow. The Marysburgh Vortex’s pull might have contributed to their misdirection.

An account of the shipwreck from the book by Hugh F Cochrane “Gateway To Oblivion 1980”

The first sign that the Quinlan was destined for a bizarre fate occurred shortly after the vessel had cleared the American shore and sailed into a fog bank. Such conditions are not too unusual in these waters during the late fall. But the seamen themselves admitted that this was an unusually thick fog, which shrouded the vessel in a wet gray blanket. With this came a rapid drop in temperature and snow crystals began to form, quickly coating the decks and hatches with a thick layer of white. Waves began to rise around the vessel and their battering became a savage fury few had ever witnessed. Thunderous waves continued to smash her hull and drive her on before the fury of the storm, and there was no telling in which direction the Quinlan was headed, for her compass had suddenly ceased to function, its needle turning lazily in its case. Lashed from all directions, the ship plummeted on, her route totally out of the control of human hands.

Shortly before noon the Quinlan slammed into the Marysburgh shore. Her masts had been snapped off, and her hull was split as violent waves pounded her to pieces on the rocks. Powerless to stop the destruction, the crew hung on to what was left of the ship while witnesses gathered on the shore frantically trying to rescue the exhausted seamen from the wreckage.

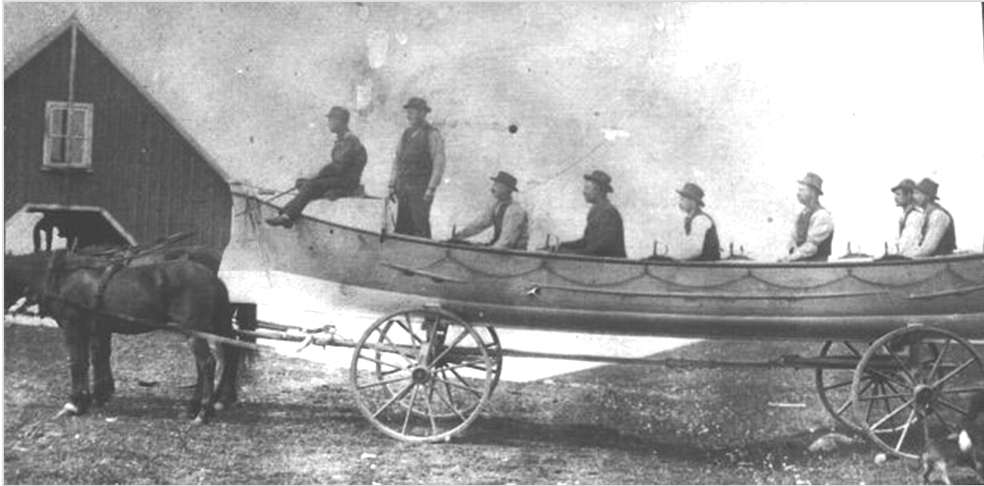

This account from the British Whig (Kingston) highlighted the courage of my great-great-grandfather, Jackson Bongard (shown at right), who played a crucial role in the rescue.

The British Whig, December 9, 1882, reported that “… before their rescue the crew were in a most perilous position for several hours but were eventually rescued through the gallant efforts of Mr. Jackson Bongard, of Long Point, and a picked crew, who heroically manned a fishing boat and brought them safely to shore. A lake captain expressed the belief that no other men could have accomplished the perilous undertaking. …” Source

Shipwrecks close to Prince Edward Point

Prince Edward Point is called the Bermuda Triangle of Lake Ontario with sharp reefs that have sunk over 100 ships over the years around Main Duck, Little Duck and Timber Islands.

There are shipwrecks close to Prince Edward Point and a sunken tug boat for scuba practice just 60 feet from the beach. Wrecks in the area include:

- The Atlasco: Wooden propeller craft-218′ x 33′ x 13′ Built in 1881 as a package freighter. She was later converted to a bulk barge. She was downbound during a gale on August17 1921 with a cargo of wire cable. She sank in about 43′ of water off the shore of Pt. Traverse. All hands escaped safely in a lifeboat. View a ship’s wheel, a rudder, winch, 4 anchors, coils of wire cable etc.

- The Fabiola: Built in 1852, this two masted schooner, was 95’x22’x 13′. Captain Danny Bates lost her on Oct.23 1900, just south of False Duck Island, on his way home from Oswego with a load of coal.No lives were lost. The hull sits upright, 55′ deep, and mostly intact. Only a section of the stern is collapsed. The winch, pump, windlass, etc can be seen..

- The Manola: The steel steamer foundered in a storm while under tow on Dec.3 1918. Built in 1890, both sections of her hull were enroute to Montreal to be rejoined for World War I service. Eleven lives were lost. The bow section lies upside down in 45′-80′ of water on the rocky floor of Lake Ontario.

- The John Randall: A propeller steam barge, 100’x23′ was built in 1905. She snak on Nov.16 1920 in School House Bay, Main Duck Island. Captain Harry Randall and his crew of four were saved and spent eight days with the lighthouse keeper on the Island. Her remains are scattered in 20′ of water in the bay.

- The Florence: This steam tug sank on Nov.14 1933 in some 30′ of water off Timber Island with no loss of life. /originally 102’x19’x13′, her hull lies torn apart 30′-40′ deep as her owners had tried to drag her to shore to salvage her engines. Intriguing rock formations and the fish that have made this wreck their home entertain those who choose to dive her remains.

- The Olive Branch:

A Wood Schooner at a depth of 95 feet built in 1871, sank in 1880. The schooner is at a depth of 92 feet. This is a stunningly gorgeous wreck. In great shape, with plenty to see, the Olive Branch is one of the best wrecks Southern Ontario has to offer. Deep enough to be cold and moderately dark, these are not things that should keep you from diving on her. Despite being on the bottom for nearly 120 years there are still artifacts to see on this wreck that would be almost unheard of anywhere in the world but in Canada. Thanks to the effort of groups like SOS (Save Ontario Shipwrecks) and POW (Preserve Our Wrecks) things have actually been returned to the wrecks they were taken from. Descending the mooring line you will be greeted with a saucer as soon as you hit the deck. It’s not a broken fraction of its former self, it is the complete, genuine article. Keep searching and you will find the sole of a shoe and iron next to it, a large anchor, masts on the starboard side in impeccable shape, gorgeous ship’s wheel still in position, and more. There is just something about the condition of the wreck, the items still to be found on it, and the details that are not there on others its age all combine to make this a truly memorable dive.

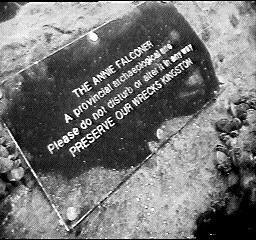

- The Annie Falconer

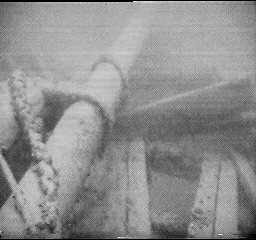

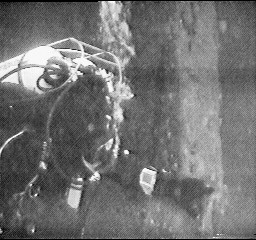

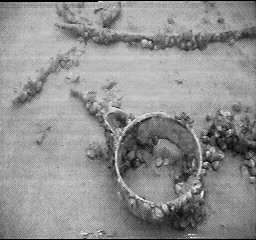

This shipwreck is a two masted schooner built of wood of 108 foot length. Built in 1867, sunk in 1904 at a depth of 79 feet. The Annie Falconer is a beautiful wreck with many details still in great shape. Not as deep as the Olive Branch which is just a few kilometres away, the conditions are otherwise virtually identical. The wooden hull is in quite good condition, aside from having its stern ripped off and lying slightly to the starboard side. The wheel is still in place on the relocated section, which is quite intact. Annie’s bow is what contains the subject of controversy. Two massive anchors were ripping the ship apart for years and what was once level decking at the front has now been wrenched wildly from the split at the tip of the bow. One of the anchors has mercifully fallen, but the other remains, doing damage which certain dive groups would love to halt by cutting it away but are reportedly being prevented from doing so by the government which does not want to see the historical site tampered with.

Immediately after descending the line you will see two small plaques (see pictures), the white one being a warning that the bow may collapse at any time and is a hazard to divers. To commemorate the work that has been done on this ship and the lives that were lost on her, there is a sizeable granite memorial at the base of the bow on the port side. You will need to get quite close to be able to read the letters carved into the black stone face, but it is well worth the effort. Despite the damage at the bow and stern this wreck is in very good condition and has several small artifacts that are easy to find. Naturally, zebra mussels prevail, having improved the visibility but taken their toll by obscuring most of the ship’s structure.

- The City of Sheboygan

A three Masted Schooner built in 1871. It sank in 1915 in 95 ft of water. The vessel is 135 ft. long and is very intact. The schooner sank in a storm with the loss of 5 lives and a load of feldspar.

Video snapshot of the plaque by Adam Rushton